In case you missed it, we launched a free product earlier this year, Mode Studio.

Free products aren't common in the world of analytics. Even less common, we launched ours after already having built a strong business around a paid product. Quite often in the last six months, we've been asked why we did it.

Though a number of things motivated us to build Mode Studio, the simplest reason we built it is the same reason we started Mode in the first place: we know analysts often don't have the tools they need to do their best work. We would consistently hear from analysts that, if it were up to them, they'd choose Mode—but it isn't up to them. Too often, IT or other departments choose the tool for analysis, and analysts have to use what they are given.

Rather than take hand-me-downs, we believe analysts should be able to choose the tools they want. So we set out to build a free version of Mode that analysts could use without having to convince other people at their company to pay for it.

A Rubik's cube, not a jigsaw puzzle

Our primary challenge was to build a free product that was useful for analysts but didn't directly compete with our paid product. It wasn't simply a which-feature-goes-where puzzle. It was more like a Rubik's Cube: a problem that, even when it looks nearly complete, might require reworking to get the right fit. We had to constantly balance conflicting requirements. And each time we made an adjustment to address one problem, it changed how we thought about the others.

In total, six questions emerged and reemerged while we were building Mode Studio. To make a smooth transition to a freemium model, we had to align all six.

Is there a market for this?

Though we already had an idea of what we wanted to do with Mode Studio, we needed to make sure we were solving a problem that was big enough to merit the work. The prevailing literature around freemium business models says that freemium products typically require a huge market of potential users to be successful. This was not the case for us.

Mode has two types of users. We have “analysts:” those who work with data directly and find answers to questions. And we have, for lack of a better name, “business users:” those who mostly interact with analysis created by others. While we estimate that there are millions of people in the world who meet our definition of an analyst, that's a fraction of the market of other famously successful freemium businesses, like Dropbox.

Analysts' colleagues, the “business users” who consume their work, include almost everyone in modern business—a market easily large enough to support a freemium business. If Mode Studio could provide an entry point to this market, we figured, the business case for a freemium strategy was much stronger.

What problem does it solve?

For someone to use a product, it needs to solve a problem. Mode Studio was no exception—it needed to either introduce people to a new way of doing something, or improve something that they already do. In other words, it couldn't just be a collection of features that were individually valuable. All its parts had to work together to solve a well-defined problem for analysts.

Based on the problems we knew analysts struggled with, we developed three ideas:

- A complete toolkit for individual analysts. We could give analysts what they need to get answers for themselves, but include only a few collaborative features.

- A collaborative tool for sharing data. We could give analysts a tool to quickly deliver data to their coworkers, but not analyze or visualize it.

- A query repository. We could build an interactive home to save SQL queries, and include features like our Github sync.

These basic functions let us draw some loose boundaries around different ideas. Each version could be a cohesive product on its own, while maintaining clear opportunities to introduce a customer to a more complete paid product. To decide which of these to build, we examined each from three angles:

- Behavior patterns of existing Mode users

- Feedback from customer surveys

- Competitive landscape for each potential product

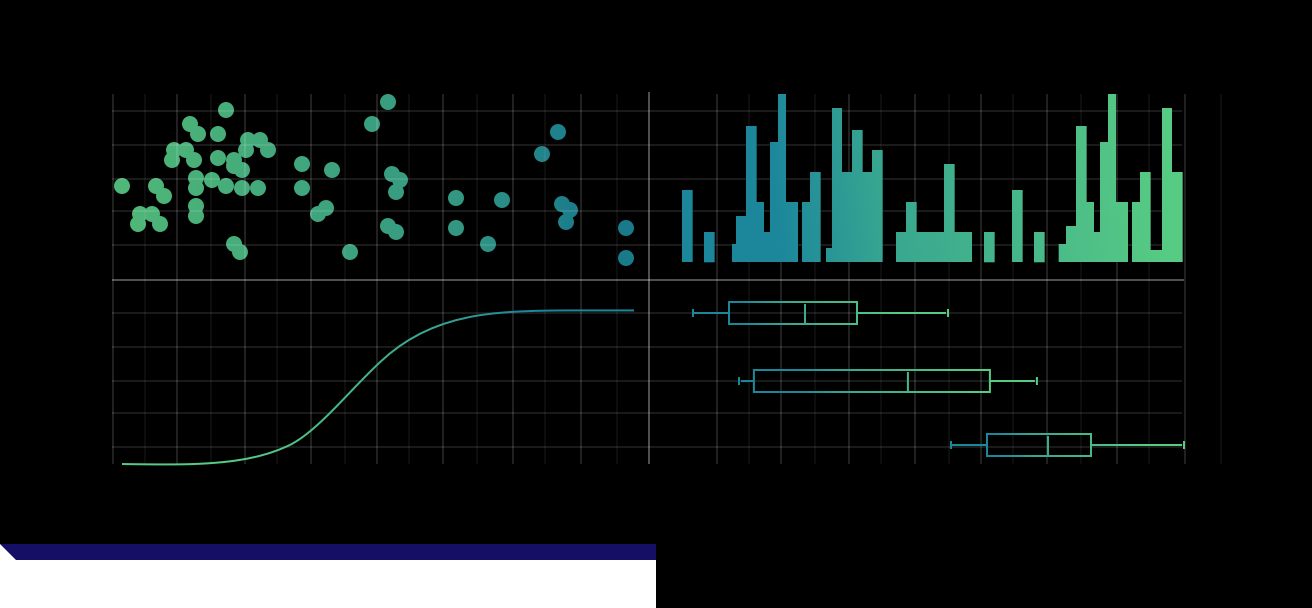

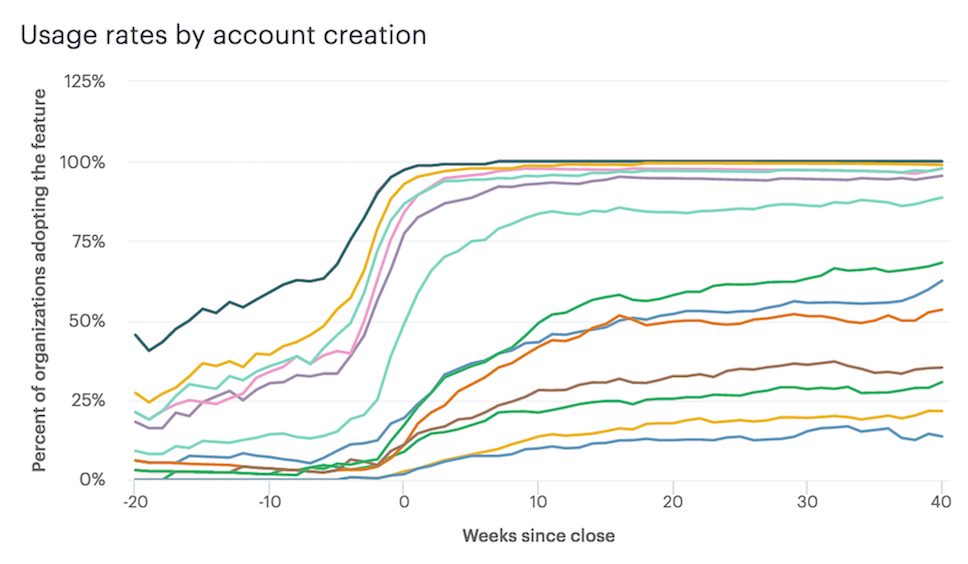

One of the most important patterns we studied was how new customers adopt different features. The graph above illustrates the percentage of customers that use each feature in the weeks before and after they purchase Mode.

The chart shows a clear divide between two types of features. The features on the upper half of the chart were used by most customers during their trial, and are adopted quickly when new customers come on board. This pattern told us that these were the features that attract people to Mode. Those features were almost entirely those that help people create analysis.

The features on the lower half of the graph tend to reveal their value more slowly. Because organizations grow over time, adoption of these features correlated with more people joining a Mode deployment. These features centered around sharing, collaboration, and administrative control.

This pattern pointed Mode Studio in a clear direction: if we wanted to build a tool that was valuable for analysts, we should focus almost entirely on helping people create analysis. A toolkit for solo analysis would not only be useful as a standalone product, but it would also clear any obstacles that might prevent people from getting to their “aha moment” as quickly as possible. Moreover, the competitive landscape showed us that a simple, well-built SQL editor could have broad appeal. By layering on visualizations and including features like integrated Notebooks, we could build a differentiated tool that satisfied that same demand.

This analysis also hinted at how to sell the paid product. Once analysts were comfortable creating work in Mode, they started to turn to collaborative features to help them distribute their analysis. By putting paywalls around these features, we could both sell something important and introduce product friction only after Mode had demonstrated clear value.

What can we build?

Once we decided to build a complete toolkit for individual analysts, we looked at what was technically feasible. Like any company, we had limited resources to invest and a deadline to hit. Despite these constraints, we didn't want to scope the project too narrowly and build a product that wasn't as valuable to analysts as it could be.

To build the best product possible in the time we had, we looked for shortcuts hidden in our current product. Mode's technical architecture made some boundaries easier to build than others. For example, we already provided more Notebook memory to premium plans than we did for standard plans. The infrastructure and logic that bifurcated Notebooks by plan type offered a natural line to split Mode Studio from our paid product. Conversely, Mode's report builder was the same for every customer. If we wanted to include a new report builder for Mode Studio, we'd have to start it from scratch.

We tried to avoid high-cost changes where possible. Each change we introduced from scratch would either add to our timeline or force us to cut other changes. Sacrificing perfect decisions that would cut against Mode's technical grain, in order to make good decisions that went with that grain, let us build the best overall product in the time we gave ourselves to build it.

What specifically is in it?

Next, we had to figure out exactly which features we should include in Mode Studio and which we should reserve for the paid product, Mode Business. Some features obviously had to be included in the free version of Mode, like our SQL editor. Others were clearly better suited for the paid version, like White-Label Embeds. But a lot of functionality fell somewhere in between. To draw the right lines, we analyzed how different types of customers were using Mode.

In particular, because our goal was to create one tier of the product for individuals and one for teams and companies, much of our analysis examined how people used features differently across differently-sized organizations.

If a feature was favored by a few specialized users, we decided to put it in Mode Studio. We figured the more we could give people for free, the better. For features that were widely used, we examined whether they were used differently in small Mode deployments compared to large ones. If we found a feature that was more valuable in large deployments or gained value as a deployment grew, it was a clear candidate for Mode Business. If it was valuable for both large and small, valuable for new customers, and fit our story of an analytics tool for individuals, we made it a candidate for Mode Studio. And if it was valuable to both but didn't make sense for solo use, we put in in Mode Business.

How do we avoid cannibalizing Mode Business?

At the end of the day, we still have to keep the lights on. If Mode Studio gave away most of the value that customers were paying for, we'd have a hard time selling Mode Business. We expected to lose some paying customers to the free product if that was what made sense for them and their business. But this project needed to create a net increase in the size of our paying customer base.

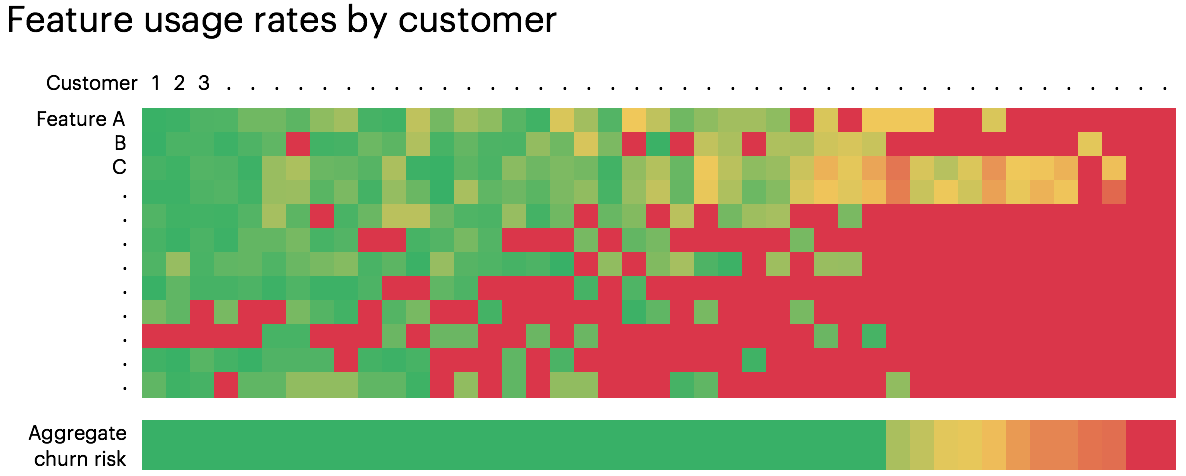

This concern made us constantly reexamine our decisions about Mode Studio. For each potential version, we analyzed how its proposed feature set was used by our current customers. The chart below shows a sample of this analysis. By measuring how often each customer used every feature we planned to put behind a paywall, we could identify who was likely to downgrade. If a significant percentage of our customer base would be put at risk, we had to redraw the lines.

In our case, this consideration never resulted in any dramatic changes to the plan. Cannibalization was near the top of our list of concerns as to how Mode Studio could go wrong, so it was in the back of our minds through the entire planning process. But we still conducted a rigorous post hoc analysis as a check against our intuition. This helped ease the natural anxiety that came with what we were doing, and assuaged the fear that this launch could potentially hurt a business that so many people have worked hard to build.

What's the narrative?

Finally, all of the boundaries we created had to make sense to our customers. Mode Studio needed to flow naturally into Mode Business with as little friction as possible. If we gerrymandered our product too much, even perfectly optimized paywalls would be confusing and could do more harm than good.

To make it easy to understand where Mode Studio ends and Mode Business begins, we focused on telling a simple story about each product. While we worked through our other questions, we looked for narratives to guide each product. As they emerged—Mode Studio for individual work, and Mode Business for teams—we favored decisions that helped us strengthen those stories over things that confused them.

Finding the right balance

Our Rubik's cube analogy breaks down in a critical way: there's no perfect solution where all the sides line up.

To tell a great story about two products, you might need to build against the existing product. To reach a larger market, you might need to accept more potential cannibalization. To deliver a product quickly, you may have to leave some features out that you wanted to include.

For us, these tradeoffs were well worth it in the end. Over the last five years, we've talked to thousands of analysts who were frustrated with the tools they were given. They were frustrated with the fact that companies often make decisions on their behalf that barely solve any of their problems. An imperfect solution to our freemium challenge was well worth progress toward solving that puzzle, the one that matters to us most.

We hope this peek into our process will be a helpful resource for those of you considering how to build your own freemium model. If you've built a freemium version of your product, we'd love to hear how you did it and how your approach compared or differed-- tweet at us at @modeanalytics or email us hi@modeanalytics.com. We love hearing from you!